Friday, March 31, 2006

Wednesday, March 29, 2006

How Evil am I?

| You Are 30% Evil |

A bit of evil lurks in your heart, but you hide it well. In some ways, you are the most dangerous kind of evil. |

More than I expected, to be true. I'm sure, however, that my cynical friend beats me in this, and gets way over 50%. By the way, he has posted a list of reviews of films he saw at the Mar del Plata Film Festival; check it if you are a cinema buff and read Spanish.

Tuesday, March 28, 2006

Steve Fuller at Crooked Timber Seminar

An "invited speaker" to the seminar not member of the Crooked Timber gang is Steve Fuller. Fuller is an expert in the philosophy and sociology of science who defends a view of science as a "social construction" and actually testified in favor of teaching Intelligent Design in the recent Dover trial, saying he was in favour of "affirmative action for fringe science", and signalling by the way an unexpected (or not) rapprochement between premodern superstitious anti-science and postmodern relativist anti-science. He has been invited to the seminar seemingly to have a voice for "the other side", although this is strange since Fuller professes to be a left-winger; to have a rational Republican defending his party would be more natural. (I'm sure rational Republicans are not as difficult to find as it seems sometimes from this side of the Atlantic).

Fuller is now lecturing in the UK, at the University of Warwick, and came to give a talk here at Nottingham some weeks ago. I went there and heard the talk (called "Theory: You can't live with it, you can't live without it") half-expecting some polemic but substantial philosophical ideas to engage with, perhaps in a blog post. I found instead that there was very little of substance in the talk: nothing to disagree with except for nit-picking details, but nothing memorable either; just some vague considerations on how "theories" that go behind the phenomena and unify them are not in vouge now in the social sciences but still are in the natural sciences. Meh. I also found Fuller to be quite an egaging speaker, who can manage easily to keep an audience attentive by using well-timed jokes and quips.

But in writing, when the resources of direct communication are not available, the defects in Fuller's thinking become clearer. Just go and read, if you can bear it, the piece he has wrote for the seminar and you'll see what I mean. It is long, long, long; it muddles around the issues never spelling them out clearly; it is pretentious and self-important, as well as vain (just at the beginning Fuller recommends Mooney that he would have benefited from reading his books). Although there are more problmes with the piece than that, I will just pick out some places where Fuller is simply wrong:

"Contrary to the democratic image that talk of ‘peerage’ connotes, relatively few members of any science are regularly involved in the process."

In my limited experience, this is quite false: most physics researchers that I know participate of paper reviewing. According to some comments in response to Fuller's post, the situation is similar in other fields.

"Mooney does not take seriously that scientists whose research promotes the interests of the tobacco, chemical, pharmaceutical or biotech industries may be at least as technically competent and true to themselves as members of the NAS or left-leaning academic scientists in cognate fields. Where these two groups differ is over what they take to be the ends of science: What is knowledge for – and given those ends, how might they best be advanced? What Mooney often decries as ‘misuse’ and ‘abuse’ of science amounts to his registering opposition to the value system in which many politicians and scientists embed scientific expertise. For example, a quick-and-dirty way to sum up the difference between scientists aligned with industrial and environmental interests is that the former are driven by solving and the latter by preventing problems. The former cling to what is increasingly called the proactionary principle, the latter to the more familiar precautionary principle."

This is an elementary mistake. The questions about matters of fact can be separeted from matters of values or policies, at least to a great degree, and it is a duty of scientists to make clear the distinction. (*) For example if an independent scientific study finds a strong correlation between smoking and lung cancer, and another scientific study paid by a tobacco company finds there is no correlation, then (at least) one of these studies must use wrong techniques of data adquisition or of statistical analysis. There is no way both can be "equally good" as science and just differ in their values as to "the ends of science", because either smoking does in fact contribute to lung cancer ot it doesn't. And I take it that Mooney's argument is that often we can find that the science that supports the industry's position is flawed on objective grounds, independently of its values and ends. Fuller misses all this and just goes on with pomo-relativistic blabber: "I don’t intend to resolve this conflict in scientific world-views here. Both lay legitimate claim to advancing both science and the public interest..."

And when Fuller reaches Intelligent Design, things get worse and worse:

"Yes, a line of descent can be drawn from high school science textbooks espousing Biblical literalism to ones now espousing intelligent design. Yes, there is probably a strong desire, perhaps even a conspiracy, by fundamentalists to convert the US to a proper Christian polity, one that is epitomized by the notorious ‘Wedge Document’ (more about which below) circulating at the Discovery Institute, the Seattle-based think-tank that has become the spiritual home of anti-Darwinism. But just how seriously should these facts be taken? After all, every theory is born in an intellectual state of ‘original sin’, as it actively promoted by special interests long before it is generally accepted as valid. It is therefore essential to monitor the theory’s development – especially to see whether its mode of inquiry becomes dissociated from its origins. So, while intelligent design theory may appeal to those who believe in divine creation, its knowledge claims, and their evaluation, are couched in terms of laboratory experiments and probability theory that do not make any theistic references. "

Oh, my, where to start here? The line about laboratory experiments is just ludicrous: not even Behe and Dembski have claimed to have experiments proving or testing intelligent design. (How could they do them?) All their arguments are theoretical, referring to the impossibility or improbability of some organic structure evolving without a Designer. And they have been shot down, proved wrong, fallacious, and at odds with both true biology and true mathematics, dozens of times already. The idea that ID might ever become "dissociated from its origins" in religion is patently absurd: it exists as a "theory" only and for the sole purpose of providing a religious apologetic and putting back religion in public schools; it is not interested in doing actual biological research or developing into a mature scientific research program. (There was a great post a couple of months ago at The Questionable Authority proving this by a simple method: it compared the number of press releases and other PR pieces of the Discovery Institute to the number of scientific publications, even counting as scientific publications some not peer-reviewed ones. The ratio was 100 : 1 .) The idea that each scientific theory is promoted by "special interests" before it gets accepted is a patent mischaracterization of the actual process of scientific discovery.

And from here on, all the part of the post that discusses evolution and Id just gets things wrong, wrong, wrong. We read that "Mooney’s repeated practice is to ask Neo-Darwinists their opinion of work by intelligent design theorists (but not vice versa). The results should surprise no one. Such opinion may indeed be expert but it is unlikely to be unprejudiced." (Well, isn't the fact that "Neo-Darwinists" as Fuller pejoratively calls biologists can refute rationally every single "argument" made by IDers a good reason to take them more seriously as experts?) There are absurd claims like "Moreover, Darwinism is philosophically ‘robust’ insofar as it has caused philosophers to alter their definitions of science to accommodate a research programme that clearly does not fit the mould of Newtonian mechanics." (If acceptance of evolution required a redefinition of science, I am not aware of it. Didn't Darwin claim to work on orthodox Baconian methods? And what does Newtonian mechanics, a paradigm for research in physics not biology, have to do with this?) Some lines are downright hilarious, such as "Thus, by no means do I wish to dismiss the Neo-Darwinian synthesis out of hand. Its construction has much to teach the social sciences, progress in which has been retarded by the sort of ‘metaphysical’ suspicions that Neo-Darwinism gladly suspends." (The most valuable outcome of the Neo-Darwinian synthesis is serving as role model for possible progress of a kind Fuller would like to see in social science! Never mind having a comprehensive and well-supported biological theory that allows us to understand how species come to be!) There are old creationist canards like there being empirical support for microevolution but not macroevolution. And so on, and on, and on...

(*) I am not defending here a philosophical dichotomy between "facts" and "values" like the one generally attributed to logical positivism and that many recent philosophers attack; just an ordinary practical distinction between "finding out how the world is in some respect" and "finding out what we ought to do about that".

UPDATE: Janet from Advenures in Ethics and Science has three great posts on Fuller's piece. In particular the last one says exactly what I try to say in my answer to Brandon in the comments, but in a much better and clearer way.

BritGrav 6 coming!

So I don't think it's likely that I'll do real-time blogging of the conference or anything like that -it will all be too much of a rush. But do expect a report on the meeting and on the most interesting talks to come out by Thursday!

Notice that I will be speaking, as will in fact all the members of our Quantum Gravity research group. Perhaps in the following days I'll manage to post something on the work I'm doing now -it seems unfair that the people coming to the conference will learn about it before than you, my Loyal Readers. Stay tuned.

More on Dumas

I love the memory of that remark, because of the way it summarises everything d'Artagnan represents in our cultural imagination: youth, adventure, romance. But nevertheless, I confess I have a deep affection for the old d'Artagnan of Vicomte, perhaps greater than the one I have for the young d'Artagnan of Musketeers as he is portrayed in the book. I am not alone in this feeling: no less an authority in adventure and romance than Robert Louis Stevenson agrees with it (and I swear that my opinions in this blog post predate my reading last year the linked essay).

Of course d'Artagnan is not really so old in Vicomte: I reckon him about 54 years. He can still use a sword better than anyone, and ride a horse at physically impossible speeds when the King's service requires it But he feels and speaks like an old man, full of wisdom and knowledge of the world, dissapointed and sad at the young generation that knows nothing of dueling and honour and thinks only of flattering the King, but never becoming cynical and keeping his ideals all the time. I remembering reading with fascination his meetings with the young Louis XIV, and feeling my young heart raptured with words like these ones protesting the unjust imprisonment of Athos:

"Oh! sire! I should go much further than he did," said D'Artagnan;

"and it would be your own fault. I should tell you what he, a man full of the

finest sense of delicacy, did not tell you; I should say - 'Sire, you have

sacrificed his son, and he defended his son - you sacrificed himself; he

addressed you in the name of honor, of religion, of virtue – you repulsed, drove

him away, imprisoned him.' I should be harder than he was, for I should say to

you - 'Sire; it is for you to choose. Do you wish to have friends or lackeys -

soldiers or slaves - great men or mere puppets? Do you wish men to serve you, or

to bend and crouch before you? Do you wish men to love you, or to be afraid of

you? If you prefer baseness, intrigue, cowardice, say so at once, sire, and we

will leave you, - we who are the only individuals who are left, - nay, I will

say more, the only models of the valor of former times; we who have done our

duty, and have exceeded, perhaps, in courage and in merit, the men already great

for posterity. Choose, sire! and that, too, without delay. Whatever relics

remain to you of the great nobility, guard them with a jealous eye; you will

never be deficient in courtiers. Delay not - and send me to the Bastile with my

friend; for, if you did not know how to listen to the Comte de la Fere, whose

voice is the sweetest and noblest in all the world when honor is the theme; if

you do not know how to listen to D'Artagnan, the frankest and honestest voice of

sincerity, you are a bad king, and to-morrow will be a poor king. And learn from

me, sire, that bad kings are hated by their people, and poor kings are driven

ignominiously away.' That is what I had to say to you, sire; you were wrong to

drive me to say it."

I actually learnt this paragraph by heart (in Spanish, of course) and recited it aloud sometimes, in the privacy of my room. Or take these words from another of the meetings, near the sad end:

"Oh!" replied D'Artagnan, in a melancholy tone, "that is not my

most serious care. I hesitate to take back my resignation because I am old in

comparison with you, and have habits difficult to abandon. Henceforward, you

must have courtiers who know how to amuse you - madmen who will get themselves

killed to carry out what you call your great works. Great they will be, I feel -

but, if by chance I should not think them so? I have seen war, sire, I have seen

peace; I have served Richelieu and Mazarin; I have been scorched with your

father, at the fire of Rochelle; riddled with sword-thrusts like a sieve, having

grown a new skin ten times, as serpents do. After affronts and injustices, I

have a command which was formerly something, because it gave the bearer the

right of speaking as he liked to his king. But your captain of the musketeers

will henceforward be an officer guarding the outer doors. Truly, sire, if that

is to be my employment from this time, seize the opportunity of our being on

good terms, to take it from me. Do not imagine that I bear malice; no, you have

tamed me, as you say; but it must be confessed that in taming me you have

lowered me; by bowing me you have convicted me of weakness.

Or (SPOILERS AHEAD) who could fail to be moved when d'Artagnan, after the death of his friends, cries at the end of the last chapter before the epilogue:

The captain watched the departure of the horses, horsemen, and carriage, then

crossing his arms upon his swelling chest, "When will it be my turn to depart?"

said he, in an agitated voice. "What is there left for man after youth, love,

glory, friendship, strength, and wealth have disappeared? That rock, under which

sleeps Porthos, who possessed all I have named; this moss, under which repose

Athos and Raoul, who possessed much more!"

He hesitated for a moment, with a dull eye; then, drawing himself up, "Forward! still forward!" said he. "When it is time, God will tell me, as he foretold the others."

He touched the earth, moistened with the evening dew, with the ends of his fingers,

signed himself as if he had been at the bénitier in church, and retook alone - ever alone - the road to Paris.

The Vicomte de Bragelonne is surely not as good a novel, as a whole, as The Three Musketeers. It is much too long (most editions cut the first two thirds and leave only the last one, calling it The Man in the Iron Mask), too full of digressions, with too many secondary and tertiary characters who pop up, dominate the scene for a few chapters, and then disappear from the plot. The supposed hero Raoul de Bragelonne is a bore: he does almost nothing but cry about Louise in the whole novel. Louise herself does little else than swoon at the King.

Monday, March 27, 2006

Sporking of The Three Musketeers, plus some reflections on beautiful children

Richelieu: Homesick, Your Majesty? You seem a little unhappy in your new home.

fourth_rose: Erm, didn't they just say they're on the brink of fighting England? So we're in 1627...

cutecoati: ...and King Louis XIII and Queen Anne have been married for twelve years!

Queen: Wah, I'm loooooooonely!

Richelieu: Austria's loss is France's gain.

cutecoati: Ok, guys, some facts. Her name is Anne of Austria because she's a Habsburg and therefore a member of the Casa de Austria, the House of Austria, but she's from the Spanish line, the daughter of King Philip III of Spain. Therefore, if anyone lost her, it would be Spain, not

Austria – apart from the fact that neither country gave a damn about marrying off another princess.

fourth_rose: Besides, if she really were Austrian, she shouldn't be homesick at all right now because she's standing in the Imperial Castle of Vienna in this scene. In a part that hadn't

been built yet in 1627, but still.

Richelieu: You have bigger problems, boy. The Duke of Buckingham is about to attack La Rochelle!

fourth_rose: Of all the places they could have picked, they took the one city that had an alliance with Buckingham.

cutecoati: Well, I guess they read something about the siege of La Rochelle in the novel, and they got the alliances backwards somehow.

King: *ogles queen* *blushes*

cutecoati: *sighs*

**

Constance: I'm sooo in love with a guy whom I saw acting like a complete idiot just once!

Queen: Tell me about it, I'm sooooooo in love with my dumbass of a husband!

fourth_rose: A-ha. Who are you and what have you done with Anne of Austria who couldn't stand her husband?

**

Rochefort: I killed your father.

fourth_rose: Thanks, everyone got it at this point.

cutecoati: That's the foyer of the Vienna State Opera, isn't it?

fourth_rose: With all this overdone 19th century decoration, it definitely is.

OK, now the serious reflections.

When I said a couple of weeks ago that I was expecting with glee the sporking of this "awful" movie, my suspicious friend reacted defending it in the comments. In a conversation we had afterwards, he made clear that his point was that a movie should be judged just by itself, and not by comparison to (and fidelity to) its historical or literary sources. Perhaps he is right in that if I hadn't read the book nor knew about it, and just saw the movie as an ordinary adventure film, I could enjoy it and not find it awful. And so perhaps my judging of the movie as a horrible corruption is not sound on aesthetic principles. However...

It seems to me that if a film deliberately presents itself to us as being an adaptation of a novel, particularly one with the cultural resonance of The Three Musketeers, it is in a way inviting us to do this kind of comparison. It is conditioning our view of it, and there is no way we can shake off our previous knowledge and get a "pure", "intrinsic" appreciation of it: seeing Richelieu as ally to the Duke of Buckingham and the Queen in love with the King brings an inevitable jolt of cognitive dissonance; "this is NOT how it is!". Even if we try hard to not see the movie in the light of the book, we will see it mediated by unconscious expectations, cultural influences and dozens of mental factors we are not aware of; a "pure" viewing is simply not possible. Rather than trying it, then, I think is better to live with our prejudices, and be as fair as we can while acknowledging them.

Of course that the mere fact that the plot from the book has been changed does not count against the movie. However, the fact that the plot has been changed in (artistically) unnecesary ways, to make it more silly, stupid and "flat", does count against the movie, and it counts against it more than a similarly stupid plot would count against an ordinary adventure movie not based on a better book. One could argue against my position that the original novel takes itself a lot of liberties with the historical record, so if inaccuracy is an aesthetic fault I should decry it in that case as well. This is answered by quoting the memorable words of Dumas, when he was accused of "raping History" in his novels; he famously replied: "True, I rape her; but I make her beautiful children." And this is it: the children produced by Dumas were much more beautiful than their mother, while those produced by Herek are much uglier than her. Rape becomes an unforgivable crime in this case.

And how beautiful were the children Dumas produced! Building up from partial records of little-known historical figures, he created a complete mythology with replaces reality and continues to enchant readers all over the world. Athos, Porthos, Aramis, d'Artagnan and Milady (and the diamond jewels!), had all a real basis, but an utterly uninteresting one, with the possible exception of d'Artagnan. But the swashbuckling, romantic, rich and colourful world that Dumas made up in his novel and its two sequels Twenty Years After and The Vicomte de Bragelonne defines our vision of 17th century France, at least for those of us who aren't professional historians, almost as much as Tolkien's works define our vision of Middle Earth. The only comparisons I can think of are Conan Doyle defining for us what we understand by "detective" or Stevenson defining what we understand by "pirate". Not coincidentally, the three are authors I loved as a child, and have grown up to love more and more.

Saturday, March 25, 2006

Friday Seminar: Quantum energy Inequalities and Local Covariance

Energy inequalities, also called energy conditions, play an important role in General Relativity. The cornerstone of GR are the Einstein equations, which describe how the spacetime geometry is determined by the presence of matter within it. The mathematical object that describes "matter" is the energy-momentum tensor Tab (also called stress-energy tensor) , and its main components are the density of energy and its pressure. Energy conditions are restrictions set on it to make it represent "physically realistic" matter: for example, the condition that energy density must be positive, or that energy density must be greater than pressure. They are needed when we want to prove the validity of a theorem for any kind of spacetime with physically realistic matter of any kind in it: for example, that too much matter too close together will result in a black hole, or that spacetimes with "closed timelike curves" (aka time machines) cannot be produced. One can write down solutions to Einstein's equations in which black holes are avoided, or in which there are closed timelike curves, but they always require "exotic" matter that violates the energy conditions.

The catch is that energy conditions are satisfied for matter as described in classical physics. Taking into account quantum theory, energy can fluctuate wildly and the object that appears in the Einstein equations is actually the mean value or expectation value of the stress-energy tensor, [Tab] (I am using brackets instead of the usual < > for the "average", as the latter is not displayed properly). It is an easy matter to show (an outline of the proof was made in the seminar) that for a quantum field this expectation value can and often will not satisfy the energy conditions. For example, in the Casimir effect, the [Tab] of the quantum electromagnetic field in its vacuum state between two conducting but uncharged plates violates the weak energy condition (WEC), one of the most widely used energy conditions, that says in intuitive terms that any observer moving along any possible timelike (i.e. not attaining the speed of light) path will never measure energy to be negative. This is not pure speculation, as theory also predicts that this vacuum energy should give rise to a tiny force between the plates, a force which has been measured.

So the questions that comes is: can the classical energy inequalities be replaced by quantum energy inequalities, conditions on [Tab] which are weaker than the classical ones but sufficent to prove all the theorems we would like to prove excluding "exotic" solutions to the Einstein equations? Chris Fewster has focused his research on this question, following pioneering work by Ford and Roman, and gave us yesterday an overview of his recent results.

Quantum energy inequalities replace a purely local condition on [Tab] at each point for an averaged condition on integrals of [Tab] over spacetime regions. They state that the integral of contracted with a sampling tensor function fab must be greater than a certain quantity; in other words, they permit negative energies but put a bound on "how negative" they can get to be. It is hoped that this sort of condition will be enough to prove all the desired results, but nobody knows for sure. ("Desired" depends on the point of view, of course; the possibility of creating wormholes, warp drives and time machines sounds fun to me! But it would create lots of complications for physics, especially the latter ones for reasons well-known to all science fiction fans.) Using powerful techniques from algebraic quantum field theory based on a principle of local covariance developed in this paper (which as I understand them roughly state that when a spacetime can be locally embedded in another one then expectation values of quantum observables can be calculated in either of both spaces) Chris and his collaborators have proved a variety of interesting results for quantum inequalities in certain kinds of curved spacetimes.

In particular, they have proved that a certain bound for the amount of negative energy measured by an observer can be established in any spacetime which has a Minkowskian (flat) region within it. This applies for example to the Casimir effect, in which the metric between the two plates is flat. Using similar techiques a collaborator has proved here similar results for spacetimes with a part isometric to a part of Scwarzschild, which applies for the exterior of stars and other compact spherically symmetric objects.

This is where the connection with my previous work appears. In my research project for my first degree I calculated the vacuum energy [Tab] of quantum fields in weak gravitational fields were the Newtonian approximation of GR holds, considering in particular the case of spherical stars. The results, which were summarized in this publication (my first and so far only paper; another post will tell you how matters are progressing with my second one) included calculating exactly the amount of negative energy measured by an observer around such a star. (I hasten to say that this was of purely theoretical interest: the energy is much too small to be really detectable by realistic experiments). So when we went for dinner to the pub with Chris and all our research group after the talk, I had an opportunity of mentioning these results to him and passing the reference, which he wasn't aware of. I hope something interesting can come out of this...

UPDATE: Post reread on Sunday morning, many typos corrected. They were caused by tiredness at the moment of original writing (which finished about 3 am)

Thursday, March 23, 2006

Incompatibility: a Google game

Some restrictions that I think are necessary to make the game interesting:

1- The words must be both in the same language (though proper names are allowed and considered to belong to all languages).

2- Both words should individually get at least 10,000 Google hits. This is to prevent tricks like using some obscure Russian name that appears only in a few pages in that language in conjunction with a very common English word like "the".

3- When I tried to start playing, I found that there are a few webpages, such as this one, that appearently try to list all words existing in all languages. I make a special rule to the effect that these pages don't count, so a search that gets only one or some of them is valid as "zero hits".

The best score I got after some time of trying was for the words: pharsalia supersymmetric, which gets 0 hits while the disjunction pharsalia OR supersymmetric gets 4,170,000. I guess that there is just no way of connecting a Latin epic poem and a symmetry relating bosons to fermions. By the way, their individual scores are respectively 963,000 and 3,120,000, which don't add to 4,170,000. I have no idea what Google is doing, but I will accept the results of the combined search with OR as official.

I have just realized that this game has a paradoxical self-defeating character: from now on there will be a Google hit for the "pharsalia supersymmetric" combination, this page! So perhaps a better way of thinking of the game, at least when its results are published on the Web, is not as discovering incompatible words but as creating, with an original act of mind, novel compatible words. I may have been the first person ever to think of Pharsalia and supersymmetry together, but from now on, the combination exists. Wouldn't you like to have that same honour for some pair of words? (Or perhaps you would, in a romantic fashion, prefer to keep some areas of the semantic space forever untouched by mankind?)

So, the challenge is set. Write your own incompatible pairs in the comments (even if they don't beat my score, I'm interested to see what you come up with). I declare the competition open for 5 days; on Tuesday evening, I will establish the winner as the first World Champion of Incompatibility!

Wednesday, March 22, 2006

The Archbishop, the Creationists, and the PZ

(I don't know who is the religious leader of the British Muslim community, if there is one, but I would like him to come out and say the same thing. In my university we see roughly once per semester the Muslim Society covering the central hall of one of the buildings with posters explaining the evil lies of evolutionism with arguments straight from the Talk Origins index. By contrast, I have not seen any Christian fundamentalism around.)

PZ Myers, however, is not happy. The very fact that the Archbishop is seen to have some special authority to make pronouncements on science makes him angry -why do people listen to a religious leader more than to science and reason? My comment is here. While on a certain level I can sympathize with this feeling, I am convinced that taking such a belligerent position is a mistake. But hell, he wouldn't be PZ if he didn't make it. PZ, with your mistakes and all, we love you.

P.S.: Chad Orzel has some good reflections on the importance of religion from a social point of view. I think he is being too mild (the opposite mistake than PZ) and I'm not sure if most religious people are so just for the social aspect of religion (cultural traditions and all that).

Monday, March 20, 2006

Darwin on the Pros and Cons of Marrying

Well, maybe it is, but then at least I am in good company, because as I found today in 3 quarks daily, Charles Darwin used the same procedure to decide whether to marry or not. The list of pros and cons he wrote is conserved, and while some parts of it are absolutely hilarious, I confess most of the similar lists I have written are much the same. I should be careful to destroy the evidence after making my decisions from now on.

So go and read it. I offer here only a preview of two "pros" and two "cons".

Pros of marrying:

-My God, it is intolerable to think of spending one’s whole life, like a neuter bee, working, working, and nothing after all—No, no, won’t do.

-Object to be beloved and played with. Better than a dog anyhow.

Cons of marrying:

-Cannot read in the evenings.

-Perhaps my wife won’t like London; then the sentence is banishment and degradation into indolent, idle fool.

Sunday, March 19, 2006

Sunday Linking

* Sean Carroll has an interesting post at Cosmic Variance on atheism in America, adding some reflections to an old discussion: whether the strategy for evolutionists in public controversies should rely more on exposing the public to religious scientists to emphasize the compatibility of theism and evolution. I had a comment on one of this these old discussions that summarizes my position, and is also somehow complementary to my previous post.

* Week 228 of John Baez's This Week's Finds classical column is out. The most interesting part for quantum gravity-interested folks is the (alas, so brief!) comment on Lauscher and Reuter's work in assymptotically safe gravity and its criticism by Distler.

* There is a fun discussion of a utility paradox at Philosohy, et cetera. I have a couple of comments.

* I also comment, on Terminator-like circular chains of causation, on this post at Siris.

* The Little Professor has posted a funny list of rules for Victorian historical fiction. Links can be found there to other lists of rules for historical fiction set in other periods.

Saturday, March 18, 2006

Are Evolution and Theism Compatible?

Most sensible people, whether theists or atheists, appear to accept that the answer to the question is affirmative. It would seem that only religious fundamentalists that think that religion consists in taking the Bible as literal and complete truth, or fanatic atheists of the "Darwin disproves God" variety, would disagree with this. (The latter are much fewer and obscurer than the former, by the way; even arch-evolutionist and atheist Richard Dawkins doesn't claim this). But how is exactly the compatibility articulated? Usually one hears things such as "Evolution is the way God works", or "Evolution occurred in a way directed by God to his ends, including the appearance of human beings". The blanket term for this views is "theistic evolution", which seems to mean more or less "I have no quarrel at all with science, and just 'top it' with my claim that the process science describes is the way of God". Thus theistic evolution distinguishes itself from a view in which evolution happened but there were some miraculous steps in it that science cannot explain, as in some kinds of ID. But ID as a general "theory" is so vague that the term means little more than "I do have quarrel with the science of evolution: science is not enough, God is needed to explain evolution". Statements of ID and theistic evolution seem sometimes very similar, and the only difference is whether the speaker wants to "pick a fight" with science or not. This was highlighted last year when a Catholic cardinal found himself at odds with the "official" Vatican position on evolution, even though a very slight change of emphasis in his words could have made them orthodox.

But how exactly can evolution be "directed" by God in a way that does not conflict at all with science? According to science, there is a complete naturalistic story that provides an explanation for the emergence of present life forms, humans included. Doesn't this contradict the claim that the faithful would like to make, that the real explanation for our existence is the will of God? Such is the argument made by Alexander Pruss in this paper, which I found via the wonderful Philosophy Papers Blog (the closest thing philosophy has to an Arxiv).

I think his arguments are mistaken, and that the matter is of importance, because belief that religion and evolution are incompatible is the major force behind oppsition to evolution and by extension to science as a whole, mostly in America but increasingly also here in Britain. I think it is therefore important to articulate the consistency of science and religion in this particular. The position I'll be trying to defend is not my own, as I am not religious, but it is the kind of position I would hold if I believed in God and cared about not contradicting science, something I think is perfectly possible. (By the way, I know that one of the most notable Christian philosophers, Alvin Plantinga, defended arguments similar to Pruss's, but I couldn't spot the reference today).

What is Pruss's argument? He says that a naturalistic evolutionary explanation is statistical in nature, and that

Evolutionary explanations do not simply state initial conditions and give laws which together entail the obtaining of the explanandum. Rather, they sketch an evolutionary scenario that includes a number of mutation events as well as claims that these mutation events led to organisms with phenotypes such as to have promoted the passing on of the mutated genotypes. A crucial part of the story is that the mutation events are not predicted from the laws and initial conditions, but it is claimed that some set of mutations and environmental interactions that would lead to the occurrence of a species containing the "notable" features (under a sufficiently general description like "intelligence" or "acute vision") is not unlikely.

The “not unlikely” part is essential to the ambitious explanations that undercut Paley-style teleological arguments...

I agree with this as a good characterization of evolution as I understand it; call it E. Pruss goes on to consider four possible ways of reconciliating it with the theistic belief T that

God intentionally brought it about, immediately or mediately, that a human species exists, and did so in such a way that the design of that human species can be attributed to that intention, in the way that the design of an artifact can be attributed to the craftsman, to borrow the analogy in Isaiah 64:8 and Romans 9:21. This implies that the existence of a species having the mental and physical features of the human species is explained by God’s intentional activity.

I will discuss only the first of these ways, which assumes a deterministic universe. Of the other three, which assume an indeterministic universe, the most important is the second (which he calles Thomism) and his argument against it is a variation of that used against the first one. The third and fourth look like philosophical hair-splitting to my unsophisticated in theology eyes.

The first option, then, is that assuming the universe to be deterministic, God could have chosen the initial conditions to be such that eventually bring about the emergence of human beings as T requires, by the natural process described by E. The reason Pruss does not think this is a good reconciliation is that according to him the existence of a theistic explanation undercuts the naturalistic one. He says:

To see this, suppose that Fred has dropped, one by one, a thousand coins from a high building, and 485 of them landed heads. We may now wonder: “Why was the percentage that landed heads between 45% and 55%?” There is a simple statistical explanation here, it seems:

(1) The probability that between 450 and 550 of the coins would land heads-up is about 99.9%, and this is why somewhere between 45% and 55% of the coins landed heads.

But suppose now we learn a further fact. Fred had calculated at what angle and velocity he would have to drop every single coin in order that the coin should land heads and the angle and velocity needed for tails. Then he carefully chose the angles and velocities so as to guarantee that between 45% and 55% of the coins would land heads-up. I submit that this extra fact falsifies (1). It falsifies (1) not by falsifying

the probabilistic claim made, since that clam is nonetheless true.

What is now seen to be false is the claim that this probabilistic fact explains the result. For it no longer does. The reason is that the probability stated in (1) is no longer conditioned on the relevant background conditions, since now a part of the relevant background condition is that Fred tossed the coins in such a way as to ensure that between 45% and 55% of them would land heads-up. The conditional probability conditioned on this piece of background knowledge is 100%, not 99.9%, and it is this conditional probability that is explanatory of the result.

So Pruss's point is that if we are theists and accept T, we cannot go on saying that E is the explanation for our existence; the deep, true explanation is T. Is this argument sound?

Well, let's take a look at what it would imply. If the truth of the statement of evolutionary theory E was really incompatible with the deeper explanation T, then the theory of evolution would have indeed the logical consequence that God does not exist, or at least that He did not deliberately intend to create humans as T states. But evolution is a scientific theory and cannot imply these claims, which are purely metaphysical and beyond the realm of science. This should make us suspect that there is something wrong in the way Pruss understands the concept of "explanation" used in E.

To go further along this way, note that all statistical explanations in science would be in similar risk of being "undercut" in the same way as E, if Pruss were correct. Suppose we explain the existence of the rings of Saturn by saying that starting from a large planet and a large number of randomly moving rocks in the Solar System the final ring configuration is "not unlikely" according to Newtonian mechanics. This is a perfectly good scientific explanation, but for Pruss it cannot be the correct one because the particular ring configuration that we got is also a consequence of the initial condition of the universe, set by God. Of course Pruss may say that he knows by revelation that the initial condition was set specifically with the intention of creating humans, not planetary rings, so the intention of God is the "true, deep" explanation undercutting the naturalistic one for the humans and not for the rings. But (leaving aside the breathtaking anthropocentrism of this claim as something perhaps inevitable in traditional forms of religion) it sets the question of whether it is valid to distiguish, in the mind of an omniscient being that creates an entire universe with its laws, which things in the universe are "intended" and which are "byproducts". From my naive point of view this seems very presumptuous. The conclusion would be that those scientific theories that give statistical explanations for things "not intended by God" are sound and compatible with theism, while those that give them for things "intended" are not so, but how is the universe parceled between these two cathegories? It is not just a matter of a few "fancy" things like humans and planetary rings; the explanation of just about any macroscopical fact is satistical in nature. Pruss seems commited either to reject all statistical explanations in science, or to make an implausible distinction, among all created things, of those that were "intended" and those that were not.

The basic response to Pruss is that the E, and all other statistical scientific explanations, claim to be explanations only in a scientific sense, not in a trascendental sense. In the spirit of methodological naturalism presupposed by science, they claim to be the best explanations that we can give that contain only testable premisses and empirically accessible objects. When science says that the explanation for our existence is E, it is always assuming this sense of explanation. Thus when Pruss gives his recommended solution to the contradiction at the end of the article:

There is, however, an approach that only weakens evolutionary theory so slightly that it yields exactly the same empirical predictions as evolutionary theory does. To do this, we adopt the physically deterministic or Molinist solution, but drop the neo-Darwinian’s claim that the statistical facts are explanatory of the notable features of the human species. The argument against the physically deterministic and Molinist approaches is compatible with the truth of all the categorical and statistical claims of evolutionary theory, but was not compatible with the higher level claim that the statistical facts are explanatory of the features. This weaker version of evolutionary theory agrees perfectly with all the predictions of standard neo-Darwinian theory, and indeed with all first order claims about what mutations happened and when, what creatures reproduced and when, and so on. It is compatible with the existence of a chain of naturalistic causes leading from a unicellular common ancestor to the human species. It is simply incompatible with the claim that all of these facts provide a statistical explanation of various features such as intelligence in the human species. (...) Interestingly, if one holds that claims of explanation belong to a meta-theory rather than to a scientific theory on its own, then this view would allow one to say that the scientific theory of evolution is entirely true. However, I believe that explanatory claims are part and parcel of a theory.

he fails to see that the sense of "explanation" in which the explanatory claim is part of the theory is the scientific or methodologically naturalistic one, not the metaphysical one that conflicts with T. To highlight this the best metaphor (which I found first in Martin Gardner's wonderful The Whys of a Philosophical Scrivener, and attributed by him to C. S. Lewis and Miguel de Unamuno if I remember correctly) is that of the universe as a story written by God. Within the story, internal explanations of things that happen can be given from previous things that happened plus the "laws of nature" within the story and statistical principles; however, from a trascendental point of view the explanation for everything that happens in the story is the will of the Author. The analogy of Fred throwing coins to the street is not apt because in it Fred's will belongs to the natural chain of causation and can be used as a scientific explanation of the distribution of coins. A trascendental intention of God cannot be used in this way.

Friday, March 17, 2006

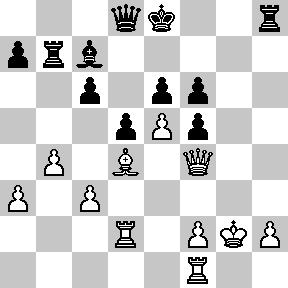

Chess Game at Chess Match

White: D. Cronshaw - Black: A. Satz

1. e4 c6 2. d4 d5 3. e5 Bf5 4. Nc3 e6 5. g4

Darn. Years ago, when I played chess virtually every day, I knew all these tricky variations of the Advance Caro-Kann by heart. Now I don't and I have to find my way by myself each time. Well, at least for this move there is no choice.

5... Bg6 6. Nge2 c5 7. Nf4

After the game my opponent suggested 7. Be3 as probably better.

7... cxd4 8. Qxd4 Nc6

I could have taken the c-pawn with the bishop, but my lag in development was beginning to look scary, so it didn't seem a good idea...

9. Bb5 Qa5 10. Nxg6

Quite a relief for me; my bishop had little play, and could eventually get trapped by h4-5.

10... hxg6 11. Bxc6

Probably my opponent wanted to prevent the simplifying 11...Qxb5 12. Nxb5 Nxd4 13. Nxd4.

11... bxc6 12. 0-0 Bb4 13. Ne2!

I was hoping for the natural 13. Bd2, which would be followed by 13...Rh3! with iniciative.

13... Bb5 14. Qf4 Rb8 15. c3 Rh3

I thought a lot of time for this move, and I am still not convinced it is the right one.The idea is to take squares from the white queen and answer the expected 16. Nd4 with 16... Rd3. On the other hand I must confess I don't know what I would have done after 16. Rd1.

16. Ng3

This made me happy, as the knight is going far from its ideal square d4 to a not very promising place. On the other hand, the rook in h3 is useless now...

16... Qd8

...so I try to make it useful by shifting sides the queen. The threat is 17... Qh5.

17. g5 Ne7 18. Kg2 Rh8 19. b4

Needed in order to develope the bishop. I seem to be losing space, but White is creating weaknesses at the same time.

19... Bb6 20. Be3 Nf5 21. Nxf5 gxf5 22. Rad1 Bc7

It is better to keek the bishop instead of exchanging it, as the White bishop is "bad" and mine can put pressure on his pawns, and indirectly, his king. 23. Bxa7 would be countered with 23... Ra8 24. Be3 25. Rxa2, followed by Qa8 controlling the a-file.

23. Rd2 Rb7 25. a3?

White is hoping to play c4, but overlooks Black's threat.

25... f6!

The position suddenly opens with disastrous consequences for White.

26. gxf6 gxf6 27. Bd4

26... c5!!

Ok, I know it is not modest to put a "!!" on a move I did myself, but I'm really proud of having seen it. It is a typical "intermediate" move: it seems pointless at the moment, but will prove crucial six moves ahead. Wait and see...

27. bxc5 fxe5 28. Bxe5 Bxe5 29. Qxe5 Qg5+ 30. Kh1

In case of 30. Kf3, I had planned 30... Rh3+ 31. Ke2 Qg4+ 32. Ke1 Rb1+ winning. Here we see the first point of 26... c5: to open the b-file for the rook. And it even has another one, which will be seen next...

30... Rxh2+ 31. Qxh2 (of course not 31. Kxh2?? Rh7 mate) Qxd2 32. Qh8+ Kd7 33. Qg7+

If I had not played 26... c5, this would be a problem for me as I would have to play 33... Kc8 and a few more checks would get him to take my e-pawn, which could be dangerous. As things stand now, this check is harmless and even makes things easier for me.

33... Kc6 34. Qg6 Qe2 35. Rg1 Kxc5 36. Qg8?

White's position is hopeless anyway, but this attempt to trap me (36... Qxf2? 37. Qc8+ Kb6 39. Rb1+) brings about a quick demise.

36... Qf3+ 37. Rg2? (37. Kh2 resisted a bit more) Qh3+ 38. Rh2 Rb1+ 39. Qg1 Rxg1+ 40. Kxg1 Qg4+ 41. Rg2 Qd1+ 42. Kh2 Qf3.

White resigns.

So the match was finally a draw at 2.5 - 2.5. But it's really a pity that we keep defaulting games because we could be doing much better, so, er... does any of you know a University of Nottingham student willing to play chess for the team?

UPDATE: Due to some weird trouble with Blogger, I thought this post had been lost and then posted the diagram as a chess problem. I have already deleted the second post as it was pointless if the whole game can be seen here.

Wednesday, March 15, 2006

A defense of the Divine Right of Kings

Monday, March 13, 2006

Monday Seminar: Bayesian Quantum Theory

Thomas hopes this formalism to have applications in quantum gravity. He makes much of an an analogy between Bayesian probability and General Relativity being both "relational" in the sense that they are compatible with Leibniz's principles of sufficent reason and of identity of indiscernibles, as discussed by Smolin. My intuitive opinion (not based, I confess, in any careful reading of the enormous material existent in this subject) is that Bayesianism is a reasonable interpretation of probability as applied to daily life and to all non-quantum contexts. Normally an assignment of probability to a proposition can only be done with respect to some given information, in a relative and not absolute way. (The probability of this coin toss falling on heads is 1/2 relative to my knowledge, but may be 1 relative to a Laplacean demon who can pre-calculate the result). But in a quantum context we do seem to have an absolute notion of probability: the probability that this particular measurement of an electron (in a pure state) will give as result spin up or down seems to be defined by quantum theory independently of any background information. (Of course it depends on the state of the electron, but normally the state in which the electron is taken as an "objective property" of it in some sense). My gut feeling is thus that Bayesianism is not an adequate interpretation of probability in quantum theory, but I am open to be convinced...

Saturday, March 11, 2006

York

The first picture shows a typical commercial street in the city centre, and also the little group of people I passed the day with. I should mention that when we were just getting into the city, I saw a place called "Gaucho" and in getting closer I saw it to be an "Argentinian steakhouse". Why is there no such thing in Nottingham???

The first picture shows a typical commercial street in the city centre, and also the little group of people I passed the day with. I should mention that when we were just getting into the city, I saw a place called "Gaucho" and in getting closer I saw it to be an "Argentinian steakhouse". Why is there no such thing in Nottingham???

After having a much-needed cofee (we had left Nottingham at 8 am) we started our city tour by walking along the medieval city walls, which are still preserved in a long part of their extension. There is where the second picture was taken.

Afterwards we went to have a quick look to the art gallery (there was a special exposition on Spanish masters like El Greco) and after that to the cathedral, York Minister, which our "guide to places of interest" claimed to be the largest gothic cathedral north of the Alps. Two

questions: is it true? if so, which is the largest south of the Alps? Whatever the answers, York Minister is certainly impressive, as you can see in the third picture (in which I couldn't fit more than one third of the building).

questions: is it true? if so, which is the largest south of the Alps? Whatever the answers, York Minister is certainly impressive, as you can see in the third picture (in which I couldn't fit more than one third of the building).

You can see that the fudge (made with whipped cream, sugar, cocoa powder, and I-can't-remember-what-else) is boiled in something that looks a bit like a cauldron from Asterix, poured on a table, then when it cools it is given shape. Afterwards it is cut into pieces for selling, each of which wheighs about 200 grams. We bought 4 pieces (for the six of us) for £ 13.99, and resisting the temptation to eat them immediately we found a place to have lunch.

After lunch we went to see Clifford's Tower, which was part of the city's fortifications in the Middle Ages. The present tower was built in the 13th century after the old one dissapeared in horrifying circumstances: Following Richard the Lionheart's coronation in 1190, a wave of persecution against the Jews took over England, and many of them were killed or forced to convert to Christianity. (To his credit as "goodie", Richard seems to have opposed and punished the persecution, although one wonders if he could not stop it quickly with his authority as King). In York the Jews took refuge in Clifford's Tower, but they were surrounded by the mob and had no chance of escaping. Then they commited mass suicide and the tower (made of timber at that time) was burnt to the ground. The story is here, together with a picture of a memorial plaque I saw today.

After that we went to see the National Railway Museum, where trains of historical interest can be seen. The most interesting were the Royal Trains made for special use of kings and queens, for example Queen Victoria. It seems that she was the first person to travel in a train with a lavatory, with inter-wagon doors, or with electrical light. I didn't take any pictures there... sorry about that. Afterwards we went back to the coach, eating the fudge in the return journey, arriving to Nottingham by 8 pm and feeling very full.

P.S. I apologize for the messy positions of text and pictures. It is the best I managed to do.

Friday, March 10, 2006

Historical movies sporked

Wednesday, March 08, 2006

Trackbackgate

The Arxiv is the server where most physics papers that come out are sent and are available for free download. It is an indespensable tool for the professional physicist, at least in the areas more related to high energy physics. Last year, the Arxiv advisory board decided to enable trackbacks on arxiv papers. This means that when going to the arxiv webpage for a paper where the title, authors, abstract and other details are filed, there would also appear a list of links to blogs that had linked to that paper.

One can see immediately advantages in this decision: it makes easier discussion between physicists, enabling the authors or others to see easily what other people are saying about any paper. But there are also obvious problems: a lot of blogs and other informal websites that might use the service are run by people who are not professional physicists, many of them even by crackpots, and the Arxiv board was concerned that enabling links from the arxiv to these pages would seem an endorsment of them, and also make unacceptably high the "noise to signal ratio" for the people that wanted serious, high quality discussion. In short, they decided they needed a filtering criterion to decide which blogs they would accept trackbacks from and which not. The criterion they decided was that to be considered "acceptable" a blogger would have to be an "active researcher", who regularly posts new papers in the arxiv. This decision, however, was not made public, presumably because of fear of loud complaints from people "left out". The system was started, and some people just found they could get trackbacks and some people found they didn't

Among those who found they didn't was Peter Woit. His blog, Not Even Wrong, is dedicated mostly to high energy physics and the mathematics related to it, with special emphasis on string theory. Woit has a very negative view of string theory and has declared in several occasions that it is, or at least it is rapidly becoming, a pseudo-science. Naturally, his opinions are strongly opposed by string theorists, many of which consider him little better than an ordinary crackpot. This is clearly not the case: Woit has a permanent position at Columbia University, has many publications on high energy physics, and has taught several courses on the subject. His opinions on string theory may be wrong or foolish, but he certainly is no crackpot. However in the past years he has published very little and has actually only two papers on the Arxiv. On these ground his blog was not considered fit to get trackbacks, even though it is one of the most read by the physics community and though it has been host to many long and high-quality discussions on string theory, loop quantum gravity and other issues in fundamental physics.

Woit thought at first that there was some technical problem responsible for him not getting trackbacks, but after many unsuccessful tries to communicate with the arxiv board and inquire what the problem was, he began to feel censored. A part of the reason for this is that string theorist Jacques Distler is a member of the board. Woit suspected that Distler was deliberately "supressing" his criticism of string-theoretical papers. Last week, Woit finally heard confirmation that trackbacs from his blog were deliberately not allowed. Still not knowing the reason for this, Woit sent a protesting letter to the arxiv board and posted it in his blog

Things started to move after that. Sean Carroll posted at Cosmic Variance supporting Woit. It was in the comments to that post that a former memeber of the arxiv board made public for first time the "active researcher" criterion, adding the words "That excludes Peter, who likes to discuss physics, but is not a researcher. It also excludes lots of other people, although I can’t remember anyone else’s name coming up. I’m not going to hazard a guess as to the role that existence of Peter’s blog played in settling on this standard." The following day Jacques Distler posted in his blog on the subject, explaining how the criterion was set and asking for possible suggestions for a better one, but refusing to discuss specifically Woit's case. Many people came into the discussion afterwards; for a variety of opinions, see Lubos Motl (who predictably defends Distler and is as insulting to Woit as usual), Chad Orzel (who criticizes the "active researcher" criterion; also here) and Georg von Hippel (who gives a fairly impartial summary). And, of course, the follow-up from Peter Woit himself

Now, what are my opinions on all this story?

First: It an obvious exageration to call it censorship, since Peter Woit can write everything he wants in his own blog, and is allowed to submit papers to the arxiv. The is no "inalienable right" to get trackbacks. The anti-string-theory crowd that is infesting comment sections in blogs making accusations of censorship is laughable.

Second: However it does seem that the criterion and the way it was interpreted (Woit himself claims to be an "active researcher" who happens to publish little) were devised on purpose to exclude Not Even Wrong from the list of "acceptable" blogs, and that this is related to Distler thinking Woit's views are of little or none scientific value. After all, there are not so many physics-related blogs that are very well known and which are in need of a carefully designed criterion (because they are not either 100% respectable like the String Coffee Table or John Baez's This Week's Finds, or 100% crackpotish like many I won't link to). The commentetor at Cosmic Variance implied that Peter Woit's case was explicitly discussed by the deciding comitee.

Third: In this case, it is inexcusable that the concsious decision was made to exclude Not Even Wrong. Regaldless of the merit of Woit's criticism of string theory, his posts are scientifically informed and give rise to interesting discussions, in which lots of well-known physicists have participated. Just to pick an example, when he commented on a paper by John Baez a long and valuable discussion followed, in which Baez himself participated. A criterion that would exclude this discussion from being trackbacked is obviously ill-designed.

Fourth: It was clearly a wrong decision to not make public the criterion immediately, giving rise to so much speculation and talk of censorship.

Fifth: The criterion itself is much too subjective to be of value. As many have asked, how many papers are needed to qualify as an active researcher? Is a graduate student who has published only a couple of papers an active researcher? (Am I?) Why not make "having a position at a physics or mathematics department" the criterion? (relaxing it to include graduate students if more inclusiveness is wanted). This is much more objective and leaves out all or almost all the crackpots.

Sixth: Is this matter really so important to justify all the electronic ink wasted on it? (Including the one in this post).

Google thinks Brokeback Mountain deserved the Oscar

Hat tip: Language Log.

UPDATE:

It's already gone. The funny thing was that Google found only 1 hit, and asked: "Did you mean 'I'm really glad trash won'?" According to Language Log, this is most likely not due to the aesthetic evaluation Google does of the movie Crash, but to the existence of Glad Trash Bags, a brand of trash bags which makes "glad trash" a more common combination on the Web that "glad crash". Ironically, the suggested combination "I'm really glad trash won" found 0 hits until bloggers started to pick up this story.

Tuesday, March 07, 2006

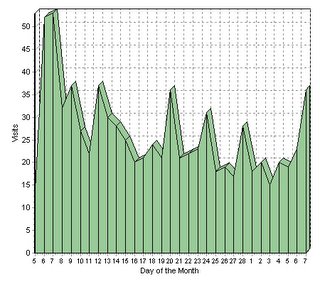

First Month Stats

Visitors per country: Sitemeter does not save this information for all visitors but only for the last 100, which are not representative. But approximately the usual composition is:

United States: 35-45%

Argentina: 15-25%

UK: 4-6%

Australia, Canada, Spain, Portugal, Finland: 2-4% each

Many other countries: 1-2% each

Overall, I am quite happy with these results for the first month. I seem to have a small band of loyal readers, about a third of them friends and two-thirds of them people I don't know. We'll see if I manage to keep the interest of these and build up a larger audience as more time passes. For the time being, thanks to all of you for coming!

Monday, March 06, 2006

Weirdest Google Search leading someone to this blog (so far)

does a queen have more entropy than rook and bishop

Now, in case you have come back still looking for an answer: I'm not sure what you think "entropy" means and I can't imagine why you would like to know this, but according to the standard physical meaning of entropy as "logaritm of the number of possible states" a queen has less entropy. During a game of chess it can be in any of 64 squares, so its entropy is log (64) = 4.158..... For a rook and a bishop the calculation is more complicated because it is not clear if the bishop is any bishop, or one in particular of the two bishops each player has (the light-squared one or the dark-squared one). If the first, then the entropy is log (64 x 63) = 8.302..... , and if the second, then it is log (32 x 63) = 7.608..... You see that in each case the queen's entropy is smaller. (I have used units in which Boltzmann's constant equals 1).

Or maybe you were not asking for the abstract, "informational" entropy of the pieces, but for the concrete thermodynamical entropy the wooden chess pieces have? Then again the rook and bishop have more entropy, simply because combined they have much more atoms than the queen, and entropy is an extensive magnitude. Assuming, of course, all the pieces are kept at the same temperature and pressure.

Hope that was useful...

Sunday, March 05, 2006

Dr. Kripkenstein: a horror story (Part 2)

The most obvious answer to Dr.K.'s argument, and the one considered at most length in the book, is that our meaning "plus" instead of "quus" can be explained in terms of dispositions. Even if before now I never thought of a sum involving numbers greater than 1000, I was and am disposed to give as answer to those sums the correct, "plus" answer instead of the "quus" one. To say that I had this disposition is to say that, if I had been asked how much is 1007 + 24, I would have given the answer 1031, and not 5, and likewise for other sums greater than 1000. This fact about my past (a fact made true by the actual, not hypothetical, condition of my brain at the past) entails that I meant my concept of "plus" to apply to the whole range of numbers, and this in turn justifies me in answering 1031 today. Let's call this conditional "if I had been asked...", p.

I think that if taken in a suitably broad fashion, a dispositionalist account of meaning must be correct. But Dr. K. has several replies to this theory, in the crude way I stated it above. I think that a more refined and nuanced statement of dispositionalism is possible, but Dr.K.'s objections are intended to be so general that they apply to any account of this kind. To put it bluntly, Kripkenstein says dispositions are not good enough to secure meaning. There are several reasons, at first glance powerful, which he gives for this. I will cite all of them, and as probably this will make the post already very long, attempt to answer to them in a Part 3 of this series.

A) My dispositions to give the addition of x and y as answer to questions of the form "how much is x + y ?" are also finite, although a much larger number than the number of actual sums I have thought of or performed. If given as a task to find the sum of two numbers so big I cannot even understand them, I am not disposed at all to give their sum as the answer; I am more "disposed" to not give any answer. If N is the largest number for which I have a stable disposition to answer correctly to sums, then the problem raised for sums greater than 1000 appears again for sums greater than N: it seems I cannot mean anything by addition as applied to such big numbers. This goes against our intuitive idea that we grasp the meaning of "plus" as applying to all numbers, even those so big we cannot think of them in a positive way.

B) As I am not perfect, there are many sums I would surely have got wrong if somebody had asked me about them. For these sums the p conditional turns out to be false. Dr. K. says that the dispositionalist account would entail we cannot make mistakes, because it gives the actual answers we are disposed to give as constituing the definition of "meaning", even if those answers are incorrect.

C) To answer A and B, we might try a "ceteris paribus" version of p: If I were in perfect mental health, and my memory capacity was extended infinitely, and......, then I would give in each case the "plus" answer. Dr. K. says these counterfactuals are so far away from the actual world that we have no way of evaluating their truth. And if "ceteris paribus" means simply "if I could do perfectly what I should do according to my meaning of +", then we are in a vicious circle.

D) [Quote] "Am I supposed to justify my present belief that I meant addition not quaddition, in terms of an hypothesis about my past dispositions? (Did I record and investigate the past physiology of my brain?)" Dr. K. is pointing here to the fact that we seem to have a "direct grasping" of the meaning of +, one that is independent of any hypothesis about what was my brain state and what dispositions it sustained when I carried out sums in the past.

E) The main problem with dispositionalism is that it gives a descriptive account of meaning, when meaning is in fact normative. Dispositions are just brute facts (neurological, for example), while the fact that I meant plus and not quus is one that intrinsically justifies my answering 1031 instead of 5, so "meaning" is a normative concept. How can the brute fact that at time t my brain state was so-and-so, justify me into anything?

Taken together, objections A-E agains dispositionalism seem to make a strong case against it. I will try to answer all these objections in Part 3; here I will just make some comments on Nagel's conclusion from the Krikpenstein argument, as he states it in The Last Word. According to Nagel, the problem with dispositionalist, behaviourist and other naturalistic accounts of meaning is basically Objection E: they lack the normative element in meaning. They try to "stand outside" our usual linguistic practice to make an "objective" description of it, but in doing so they miss the normative element which is only seen "from the inside". Nagel concludes that my meaning addition by "plus" is an irreducible normative fact: "I do mean addition by 'plus'; it is in a perfectly good sense a fact about me. But in response to the question 'What fact?' it is a mistake to try to answer except perhaps by further defining 'addition' for someone who may be unfamiliar with the term. It is a mistake to try to escape from the normative, intentional idiom to a plane that is 'factual' in a different, reductive sense". (I have copied the quote from this essay which discusses these same issues, as I have the book in a Spanish translation). I think this leaves intentionality as a complete mystery. The facts of meaning, insofar as they are definite facts, should at least supervene on specifiable natural facts*, and in that sense be reducible to them. My full answer to Objection E will come in the next post in this series; for the moment it is enough to note this link between Dr. K.'s argument and Nagel's philosophy as I have described it in my review of his book.